Taigen Dan Leighton, along with members of the Ancient Dragon Zen Gate and the Mountain Source Sangha, participated during June, 2007 in a pilgrimage in northern China to monasteries and other important sites in the history of Chan Buddhism. The contributions to Zen made by Bodhidharma, Zhaozhou (Joshu in Japanese), Huike (the Second Ancestor), and Linji (Rinzai in Japanese), and visits to temples associated with each of them, were the central focus of the trip. Additionally, we visited temples important to the early development of Buddhism in China; the Longmen (Dragon Gate) Grottoes with many Buddhist statues; Tiananmen Square; the Forbidden City; the Great Wall; the Oracle Bones Museum in Anyang; and in the ancient capital Xian: the Wild Goose Pagoda, the Great Mosque, and the Terra Cotta Warriors.

The pilgrimage was led by Andy Ferguson, author of Zen’s Chinese Heritage, the Masters and Their Teachings (Wisdom Publications), and organized by South Mountain Tours (southmountaintours.com). Andy, together with Bill Porter (Red Pine), has done much to discover ancient Chan sites in China and to make them available to Western visitors. Along with Taigen, from Ancient Dragon Zen Gate were Mike Bieniek and Debra Callahan (who has come from Pittsburgh to participate in ADZG seminars), and from Mountain Source Sangha came Dale McKenzie from San Rafael and Arlen Tang from San Francisco.

We stayed for three days at Cypress Grove Monastery in Bailin, where Zhaozhou practiced during the last forty years of his very long, 120-year life. Called Guanyin-yuan [Jpn: Kannon-in] after the bodhisattva of compassion during Zhaozhou’s life, Cypress Grove Monastery is now named for the grove descended from the famous Cypress tree in one of the stories about Zhaozhou. It is also the place where Master Wumen [Jpn: Mumon] assembled the koans comprising The Gateless Barrier, one of the principal koan collections used in Zen today.

Zhaozhou’s stupa, containing his ashes, is the spiritual epicenter of Cypress Garden. A magnificent 9th century carved stone memorial that towers over all other local buildings, Zhaozhou’s stupa overlooks cypress trees that are said to be descendants of the cypress tree to which Zhaozhou referred in his recorded sayings. Chinese pilgrims offered incense to Zhaozhou at his stupa throughout our stay at Cypress Grove. Meditating in the cypress grove next to the stupa and circumambulating the stupa at sunset were some of the most moving experiences of the pilgrimage.

The group also practiced zazen at the Samantabhadra Meditation Hall at Cypress Grove. One of the 120 practicing monks at Cypress Grove instructed us on Chinese methods of zazen, drinking tea, and walking meditation (quite different from the Japanese Soto form of kinhin we do). The most important lesson was that, while details differ, the hearts of the Chinese and Japanese Zen practices are the same.

Taigen, Tonen Sara O’Connor (of the Milwaukee Zen Center) and Genmyo Elihu Smith (of the Prairie Zen Center in Springfield, Illinois) each delivered Dharma talks at the meditation hall in Cypress Grove. Taigen provided an introduction to Zhaozhou’s life story, his long relationship with his teacher, Nanquan [Jpn: Nansen], his place in the Zen development, and his ongoing influence on Zen. Taigen emphasized the playfulness and directness in Zhaozhou’s teaching, and how Zhaozhou deviated from Confucian orthodoxy by being open to learning from children and teaching his elders. Taigen observed that Zhaozhou is the subject of more koans than any other Zen teacher. Taigen focused on the story that he has been teaching about recently in our Ancient Dragon Zen Gate Thursday evening classes, the story in which–when asked by a monk what was the intention of Bodhidharma (the founder of Chan) in coming from the West, Zhaozhou responded, “The cypress tree here in the garden.”

Tonen presented the story in which Zhaozhou locks himself inside the monks’ hall, yells “fire” while refusing to let his putative rescuers into the hall, and leaves the monks’ hall only after receiving from Nanquan through the window of the monks’ hall a useless key that Zhaozhou does not actually need to free himself. Tonen re-emphasized Taigen’s observations about Zhaozhou’s and Nanquan’s humor, speculating that Zhaozhou and Nanquan had probably conspired to create this scene before enacting it, and that they had probably had a good laugh after Zhaozhou emerged from the monks’ hall. Tonen interpreted the story to mean that no teacher can unlock the barriers to self-liberation that each student creates for himself teachers can only offer tools that may, or may not, be helpful to their students.

Genmyo presented Case 19 from The Gateless Barrier, in which Zhaozhou asks Nanquan “What is the Way?”, to which Nanquan answers “Ordinary Mind is the Way”. Genmyo emphasized the directness of experience as the core of this koan, citing Case 3 of The Gateless Barrier, in which Master Gutei (Judi in Chinese) uses one finger to teach Zen, as another example of the theme of the Ordinary Mind story.

Our group was invited to attend services at the Buddha Hall at Cypress Grove every morning and evening. The beautiful sound of the chanting and the graceful movements of the monk-celebrants at these services were highlights of the trip.

The Abbot of Cypress Grove monastery, Minghai, met with us twice during our stay. The Abbot discussed the revival of Chinese Buddhism after the Cultural Revolution, the nuances of the services that we had attended, and his belief that the core of Zen practice is “open mind, self faith.” The Abbot expressed his hope that in the future, there would be no dominant nation that instead, all nations would work together with common goals.

We also toured the Second Ancestor’s Village, a very small rural community that is the site of a temple associated with Huike that was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Most of the population of the Second Ancestor’s Village greeted our 10-car caravan when we arrived, and Abbot Huike served tea and watermelon before we toured the ruins of the Second Ancestor’s Temple. Our purpose here was to support the re-building of an historically important temple destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and to draw to the attention of Chinese authorities the conditions in which the population of the Second Ancestor’s Village live, and our awareness of those conditions. We received no friendlier or more enthusiastic greeting during our trip.

We visited three sites associated with Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan Buddhism: Shaolin Temple, Bodhidharma’s cave, and Empty Form Temple. Shaolin Temple features traditional temple buildings as well as large modern facilities honoring the legend that Bodhidharma invented kung-fu. Bodhidharma’s cave, where Bodhidharma meditated for nine years after arriving in China, looks out over Shaolin Temple from the top of one of the surrounding mountains. Many in our group will remember the arduous trek to the cave on the mountaintop as the highlight of the trip.

Bodhidharma founded and taught at Empty Form temple after leaving Shaolin. Empty Form Temple is the site of Bodhidharma’s stupa, several temple buildings and housing for the monks who live there. We offered incense at Bodhidharma’s stupa and chanted the Heart Sutra before touring the temple grounds with Abbot Yanshi. The Abbot also gave a Dharma talk in which he described the re-dedication of the temple in the 1990’s, at which a hundred thousand Chinese worshippers performed full prostrations up the entire length of the road that leads to the temple (a few miles). The Abbot told us that everyone who shares Bodhidharma’s Mind owns Empty Form temple, and that we are always welcome there.

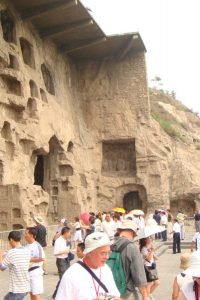

The pilgrimage included stops at a number of other important Buddhist sites: White Horse Temple, the first Buddhist temple built in China, was where the first sutras arrived from India in the first century C.E. carried by two white horses. The Japanese Soto founder Dogen named his monastery Eiheiji after the Japanese name, Eihei, for the era when this White Horse Temple was founded, and so he is now known as Eihei Dogen because of this temple. At Linji [Jpn: Rinzai] Temple, a residential monastery that includes Linji’s stupa, we offered incense, chanted and observed the more than forty monks in training as they chanted services. The Lama Temple, a Tibetan-style temple in Beijing, was favored by many emperors. At Yunju Si, monks inscribed all the sutras onto stone tablets, which were then buried in order to preserve the Dharma during the future persecutions they anticipated, and which were uncovered only within the last century. At the Wild Goose Pagoda in Xian during the 7th century 1335 volumes of sutras were translated from Sanskrit to Chinese by the great Chinese monk Xuanzang, after his seventeen year pilgrimage to India. Finally, at Longmen Grotto thousands of magnificent Buddhist images are carved on a cliff alongside the Yellow River.

-by Mike Bieniek with Taigen Leighton (all photos by Mike Bieniek)